Non-Native Forest Insects and Diseases

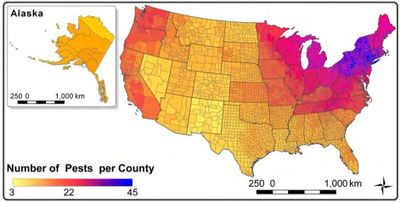

Since European settlement began in North America, nearly 500 non-native tree-feeding insects and disease-causing pathogens have been introduced into the United States. As the map illustrates??, the highest numbers are in the Northeast, upper Midwest, and Mid-Atlantic. However, the Pacific Coast states are catching up. And every county has at least three damaging non-native pests. Other damaging pests have been introduced to U.S. islands in the Pacific and Caribbean.

What Are the Major Pests?

About 90 of these have caused notable damage to our trees (Guo et al. 2019).

Introductions continue apace. Over the past 30 years, numerous new pests have been detected on the Continent and islands. These include

· At least 30 non-native species of wood- or bark-boring insects (Scolytinae / Scolytidae) (Haack and Rabaglia 2013) – including the highly damaging redbay ambrosia beetle, polyphagous shot hole borer, Kuroshio shot hole borer, Mediterranean oak borer.

· In addition,

o Eight Cerambycids such as Asian longhorned beetle (Wu et al. 2017);

o Seven Agrilus, including emerald ash borer and soapberry borer, to which I add the goldspotted oak borer which has been transported from Arizona to California (Digirolomo et al. 2019; and R. Haack, pers. comm.

o Sirex woodwasp;

o Pests of palm trees, e.g., red palm mite, red palm weevil, South American palm weevil;

o Spotted lanternfly; and

o Beech leaf disease.

· In addition, pests on America’s Pacific Islands:

o ‘Ohi‘a rust;

o Cycad scale;

o Cycad blue butterfly;

o Erythrina gall wasp;

o Two Ceratocystis pathogens that cause rapid ‘ōhi‘a death; and

o Coconut rhinoceros beetle

To prevent introduction of the Asian gypsy moth, authorities have carried out approximately 25 eradication programs targetting introductions of the pest (USDA 2014; plus pers. comm.).

map showing numbers of non-native forest pests by county; from

What Kind of Damage Do they cause?

For more information about individual pests mentioned below, visit www.dontmovefirewood.org and click on “Invasive Species”.

Non-native pests have nearly eliminated some tree and shrub species and put others under severe threat. Some of these threatened species are widespread (e.g., chestnut, ‘ōhi‘a), others create unique biological communities (e.g., whitebark pine, eastern hemlock, swamp bay); others have always been uncommon (e.g., butternut).

In the eastern deciduous forest, many if not most tree species are depleted or under threat, including ash, butternut, chestnut, dogwood, elm, hemlock, maples, and oaks. The cumulative environmental and economic impacts have not been calculated.

Severe depletion of tree species damages the wider environment by, inter alia, depriving invertebrates and vertebrates of sources of food and shelter, altering leaf litter depth and litter and soil chemistry, changing water infiltration rates, and opening gaps that can be invaded by invasive plants.

If one focuses on economics, the highest costs arise from cities’ efforts to manage their dead and dying trees. Local governments across the country spend an estimated $1.7 billion each year to remove trees killed by the emerald ash borer or other pests. Homeowners spend an additional $1 billion to remove and replace trees. In addition, they lose $1.5 billion per year in value of their property (Aukema et al. 2011). These amounts will rise substantially as pests continue to spread.

ash tree killed by emerald ash borer damages house in Michigan; photo provided by former Ann Arbor

What trees are most affected?

The most recent attempt to set priorities for conservation efforts (Potter et al. 2019) lists the following 15 tree species as most in need of protection. I have named the principal threat:

· Florida torreya (Torreya taxifolia) – pathogen (a newly described Fursarium);

· American chestnut (Castanea dentata) – exotic pathogen;

· Allegheny chinquapin (C. pumila) – exotic pathogen;

· Ozark chinquapin (C. pumila var. ozarkensis) – exotic pathogen;

· Redbay (Persea borbonia) – exotic disease complex;

· Carolina ash (Fraxinus caroliniana) – exotic insect;

· Pumpkin ash (F. profunda) – exotic insect;

· Carolina hemlock (Tsuga caroliniana) – exotic insect;

· Port-Orford cedar (Chamaecyparis lawsoniana) – exotic pathogen;

· Tanoak (Notholithocarpus densiflorus) – exotic pathogen;

· Butternut (Juglans cinerea) – exotic pathogen;

· Eastern hemlock (Tsuga canadensis) – exotic insect;

· White ash (Fraxinus americana) – exotic insect;

· Black ash (F. nigra) – exotic insect; and

· Green ash (F. pennsylvanica) – exotic insect.

That same effort is under way for Hawai`i and the U.S. Caribbean islands. So far, it is clear that Hawai`i’s most widespread tree, ‘ōhi‘a, is under dire threat from at least two pathogens.

dead whitebark pine at Crater Lake National Park - killed by white pine blister rust

How do tree-killing pests reach North america?

The insects and plant pathogens that are killing North America’s trees reach here primarily as larvae or spores riding undetected in several kinds of imports:

· Crates, pallets, and other kinds of packaging made of wood. Examples include Asian longhorned beetle, emerald ash borer, redbay ambrosia beetle; and

· Living plants imported for our use, often as ornamentals in our gardens. Examples include hemlock woolly adelgid, sudden oak death pathogen, and probably beech leaf disease.

Less commonly, such pests arrive on ship superstructures and hard-sided cargo (including shipping containers), in decorative items made of wood, and even on metal and stone imports (separate from any packaging). An example in the first group is the Asian gypsy moth; and example in the last group is the spotted lanternfly.

Insects and pathogens enter North America via international trade

How do pests spread?

Many pests spread naturally, by flying or floating on the wind or attaching to migratory birds. Examples include gyspy moths, chestnut blight, and hemlock woolly adelgid.

Many pests have been spread from one state or region to another on ornamental plants moving in interstate trade. A recent example is the sudden oak death pathogen; in spring 2019, plants potentially infested by this pathogen were shipped to retail outlets in 18 states http://nivemnic.us/updates-sod-infested-plants-shipped-widely-possible-detections-of-beech-leaf-disease-in-connecticut-and-new-york/

Other pests, especially wood-borers, are easily spread in firewood – both commercial shipments and individuals taking firewood from dead or dying trees from their own properties https://www.dontmovefirewood.org/

There are also examples of pests being spread by woodturners and wood workers who take home logs for carving. Two examples are redbay ambrosia beetle and walnut twig beetle/thousand cankers disease.

firewood - one of the most likely pathways by which insects spread

t

What has been done?

The U.S. government has worked for a century to prevent introduction and spread of damaging plant pests, including those which attack trees. These programs are administered primarily by a branch of the U.S. Department of Agriculture, the Animal and Plant health Inspection Service (APHIS). (APHIS' responsibilities are described briefly under "Invasives 101" on this website.)

Beginning in the early 20th century, the U.S. adopted a series of policies aimed at curtailing plant pest introductions. The current statute, the Plant Protection Act (PPA) [7 U.S.C. §7701, et seq.]. https://www.aphis.usda.gov/plant_health/plant_pest_info/weeds/downloads/PPAText.pdfwas adopted in 2000. The PPA authorizes the Secretary of Agriculture to regulate the importation or movement in interstate commerce of any plant, plant product, biological control organism, noxious weed, article, or means of conveyance, if the Secretary determines that the prohibition or restriction is necessary to prevent the introduction into the U.S. or the dissemination of a plant pest or noxious weed within the U.S.

Under this authority, APHIS has adopted major regulations aimed at reducing introduction forest pests via various pathways, including logs and lumber from various geographic regions (Title 7 CFR Pt. 319.40), https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/CFR-2019-title7-vol5/xml/CFR-2019-title7-vol5-part319.xml#seqnum319.40-1 wood packaging (Title 7 CFR Pt. 319.40), https://www.ecfr.gov/cgi-bin/text-idx?c=ecfr&sid=00d469d94f7cdf9267b8b8ae6603c25f&tpl=/ecfrbrowse/Title07/7cfr319_main_02.tpl-- superstructures of ships from certain Asian countries, and imported plants (USDA APHIS 7 CFR; Federal Register Vol. 83, No. 53). https://www.federalregister.gov/documents/2018/03/19

APHIS also participates actively in several international bodies intended to prevent the global movement of plant pests, the most important being the International Plant Protection Convention (initially adopted in 1951; significantly revised in 1996); and North American Plant Protection Organization (formed in 1976). These organizations have adopted important “standards” aimed at reducing introduction forest pests via wood packaging (ISPM#15) https://www.ippc.int/static/media/files/publication/en/2016/06/ISPM_15_2013_En_2016-06-07.pdfand imported plants https://www.ippc.int/en/publications/636/and https://www.nappo.org/english/products/regional-standards/regional-phytosanitary-standards-rspms/rspm-24/ and ship superstructures https://www.nappo.org/english/products/regional-standards/regional-phytosanitary-standards-rspms/rspm-33/

Despite APHIS’ efforts, tree-killing pests continue to arrive in the U.S. – thus demonstrating that these efforts have failed to provide the necessary level of protection. See the blogs on this website and my earlier “Fading Forests” reports at http://treeimprovement.utk.edu/FadingForests.htm Or go here to obtain several 2-page fact sheets that describe the pathways by which forest pests enter the U.S. or are spread within the country; economic impacts of these pests; and responsibilities of federal agencies.

The USDA Forest Service is responsible for managing the hundreds of non-native tree-killing pests that have established and for assisting APHIS in developing and implementing effective programs to counter invading pests and the pathways by which they enter the U.S. or spread once in the country. The Service’ State and Private Forestry program assists state and private forest managers. Again, these responsibilities are described briefly under "Invasives 101" on this website.

The USDA Forest Service has undertaken several major efforts to define and demonstrate the impact of non-native pests and to set priorities for conservation efforts – see the National Insect and Disease Risk Assessment (Krist et al. 2014); a series of articles by Randy Morin, Sandy Liebhold, and others; and Project Capture (Potter et al. 2019).

A book-length study of invasive species impacts to America’s forests – ranging from feral hogs to invasive plants – is expected to be published later this year. Watch the blog for an announcement when it is released.

Despite the effort put into these assessment efforts by the Forest Service, however, neither the Forest Service nor other stakeholders has followed through by providing adequate resources for long-term restoration (see below).

Examining wood packaging with evident pest damage

what can we do?

To prevent tree-killing pests’ introduction and spread, CISP advocates for the following actions:

· APHIS tighten and vigorously enforce its regulations on wood packaging and imported plants to minimize the number of pests that use these pathways to reach the U.S.

· American companies hold their foreign suppliers responsible for complying with conditions under which wood packaging and plants may be shipped to the U.S.

· APHIS and the Bureau of Customs and Border Protection vigorously enforce requirements that ships from Asia be free of gypsy moth eggs.

· APHIS collaborate with the states and nursery industry to ensure that living plants shipped from one part of the country to another are free of pests.

· APHIS collaborate with the states, firewood industry, camping organizations, and others to ensure that firewood does not transport pests.

· APHIS, the states, woodworkers and the timber industry collaborate to ensure that logs they transport do not transport pests.

Success in preventing the introduction and spread of tree-killing pests depends on access to improved tools for finding, monitoring, and controlling the pests and for restoring tree species to the forest. Therefore, CISP will also advocate for adequate funding for research and methods development programs carried out by APHIS, the USDA Forest Service, and other federal, state, and academic entities.

Members of Congress work for us! Tell them what you think.

restoring trees already under pressure by pests

As we note above, more than a dozen species of trees on the Continent and additional species on the islands are under severe threat from non-native pests. Prevention of pest introductions will not restore these species. Instead, we need additional programs to research, develop, and implement such long-term strategies as biological control of the pest and breeding resistance in the at-risk tree species. A bill to create such programs has been introduced in the Congress. See Bonello et al. 2019.

transgenic American chestnut planted in Fairfax County, Virginia

sources

Aukema, J.E., B. Leung, K. Kovacs, C. Chivers, K. O. Britton, J. Englin, S.J. Frankel, R. G. Haight, T. P. Holmes, A. Liebhold, D.G. McCullough, B. Von Holle..2011. Economic Impacts of Non-Native Forest Insects in the Continental United States PLoS One September 2011 (Volume 6 Issue 9)

Bonello, P., F.T. Campbell, D. Cipollini, A.O. Conrad, C. Farinas, K.J.K. Gandhi, F.P. Hain, D. Parry, D.N. Showalter, C. Villari, and K.F. Wallin. 2019. Invasive tree pests devastate ecosystems – A proposed new response framework. Frontiers http://journal.frontiersin.org/article/10.3389/ffgc.2020.00002/full?&utm_source=Email_to_authors_&utm_medium=Email&utm_content=T1_11.5e1_author&utm_campaign=Email_publication&field=&journalName=Frontiers_in_Forests_and_Global_Change&id=510318

Digirolomo, M.F., E. Jendek, V.V. Grebennikov, O. Nakladal. 2019. First North American record of an unnamed West Palaearctic Agrilus (Coleoptera: Buprestidae) infesting European beech (Fagus sylvatica) in New York City, USA. European Journal of Entomology. Eur. J. Entomol. 116: 244-252, 2019

Guo, Q., S. Fei, K.M. Potter, A.M. Liebhold, and J. Wenf. 2019. Tree diversity regulates forest pest invasion. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. www.pnas.org/cgi/doi/10.1073/pnas.1821039116

Haack, R.A. and R.J. Rabaglia. 2013. Exotic Bark and Ambrosia Beetles in the USA: Potential and Current Invaders. CAB International 2013. Potential Invasive Pests of Agricultural Crops (ed. J. Peña)

Krist, F.J. Jr., J.R. Ellenwood, M.E. Woods, A. J. McMahan, J.P. Cowardin, D.E. Ryerson, F.J. Sapio, M.O. Zweifler, S.A. Romero 2014. National Insect and Disease Forest Risk Assessment. United States Department of Agriculture Forest Service Forest Health Technology Enterprise Team FHTET-14-01

Potter, K.M., Escanferla, M.E., Jetton, R.M., Man, G., Crane, B.S. 2019. Prioritizing the conservation needs of US tree spp: Evaluating vulnerability to forest insect and disease threats, Global Ecology and Conservation (2019), doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/

United States Department of Agriculture, Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service. 2014. Asian gypsy moth pest alert https://www.aphis.usda.gov/publications/plant_health/content/printable_version/fs_phasiangm.pdf and pers. comm.

Wu,Y., N.F. Trepanowski, J.J. Molongoski, P.F. Reagel, S.W. Lingafelter, H. Nadel, S.W. Myers & A.M. Ray. 2017. Identification of wood-boring beetles (Cerambycidae and Buprestidae) intercepted in trade-associated solid wood packaging material using DNA barcoding and morphology Scientific Reports 7:40316

Copyright © 2023 Center for Invasive Species Prevention - All Rights Reserved.

Powered by GoDaddy Website Builder